-

Euclid And His Modern Rivals

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson

Hardcover (Kessinger Publishing, LLC, Sept. 10, 2010)This scarce antiquarian book is a facsimile reprint of the original. Due to its age, it may contain imperfections such as marks, notations, marginalia and flawed pages. Because we believe this work is culturally important, we have made it available as part of our commitment for protecting, preserving, and promoting the world's literature in affordable, high quality, modern editions that are true to the original work.

-

Euclid and His Modern Rivals

Lewis Carroll

eBook (Dover Publications, March 5, 2014)The author of Alice in Wonderland (and an Oxford professor of mathematics) employs the fanciful format of a play set in Hell to take a hard look at late-19th-century interpretations of Euclidean geometry. Carroll's penetrating observations on geometry are accompanied by ample doses of his famous wit. 1885 edition. Z

Z

-

Euclid and His Modern Rivals

Lewis Carroll, Mathematics

Hardcover (Dover Publications, March 29, 2004)The author of Alice in Wonderland (and an Oxford professor of mathematics) employs the fanciful format of a play set in Hell to take a hard look at late-19th-century interpretations of Euclidean geometry. Carroll's penetrating observations on geometry are accompanied by ample doses of his famous wit. 1885 edition. Z

Z

-

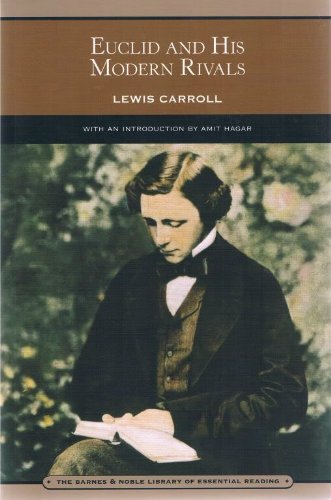

Euclid and His Modern Rivals

Lewis Carroll, Amit Hagar

Paperback (Barnes & Noble, March 15, 2009)British maverick Lewis Carroll successfully combines his inimitable sense of humor with his transparent logical reasoning in one of the most interesting books ever written about mathematical pedagogy, "Euclid and His Modern Rivals". Required reading not only for experts in mathematical curriculum development but also for all of Carroll's admirers, this book is expertly written with razor-sharp wit. It is hard to find a funnier or more enjoyable book on such a subject that is commonly regarded as academic and far removed from everyday life; no one but the author of "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland" could rise to this kind of challenge and walk away triumphant.

-

Euclid and His Modern Rivals

Charles L. Dodgson

Paperback (Cambridge University Press, July 20, 2009)Euclid and His Modern Rivals is a deeply convincing testament to the Greek mathematician's teachings of elementary geometry. Published in 1879, it is humorously constructed and written by Charles Dodgson (better known outside the mathematical world as Lewis Carroll, the author of Alice in Wonderland) in the form of an intentionally unscientific dramatic comedy. Dodgson, mathematical lecturer at Christ Church, Oxford, sets out to provide evidentiary support for the claim that The Manual of Euclid is essentially the defining and exclusive textbook to be used for teaching elementary geometry. Euclid's sequence and numbering of propositions and his treatment of parallels, states Dodgson, make convincing arguments that the Greek scholar's text stands alone in the field of mathematics. The author pointedly recognises the abundance of significant work in the field, but maintains that none of the subsequent manuals can effectively serve as substitutes to Euclid's early teachings of elementary geometry.

-

Euclid And His Modern Rivals

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson

Paperback (Kessinger Publishing, LLC, March 4, 2009)This scarce antiquarian book is a facsimile reprint of the original. Due to its age, it may contain imperfections such as marks, notations, marginalia and flawed pages. Because we believe this work is culturally important, we have made it available as part of our commitment for protecting, preserving, and promoting the world's literature in affordable, high quality, modern editions that are true to the original work.

-

Euclid and his modern rivals,

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson

Paperback (Dover Publications, March 15, 1973)The author of Alice in Wonderland (and an Oxford professor of mathematics) employs the fanciful format of a play set in Hell to take a hard look at late-19th-century interpretations of Euclidean geometry. Carroll's penetrating observations on geometry are accompanied by ample doses of his famous wit. 1885 edition.

-

Euclid and His Modern Rivals

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson

Hardcover (Lindemann Press, Nov. 4, 2008)EUCLID AND HIS MODERN RIVALS by CHARLES L. DODGSON. Originally published in 1879. PROLOGUE: THE object of this little book is to furnish evidence, first, that it is essential, for the purpose of teaching or examining in elementary Geometry, to employ one text book only secondly, that there are strong a priori reasons for retaining, in all its main features, and specially in its sequence and numbering of propositions and in its treat ment of parallels, the Manual of Euclid and thirdly, that no sufficient reasons have yet been shown for aban doning it in favour of any one of the modern Manuals which have been offered as substitutes. It is presented in a dramatic form, partly because it seemed a better way of exhibiting in alternation the argu ments on the two sides of the question partly that I might feel myself at liberty to treat it in a rather lighter style than would have suited an essay, and thus to make it a little less tedious and a little more acceptable to unscientific readers. In one respect this book is an experiment, and may chance to prove a failure I mean that I have not thought . it necessary to maintain throughout the gravity of style which scientific writers usually affect, and which has some how come to be regarded as an f inseparable accident of scientific teaching. I never could quite see the reason ableness of this immemorial law subjects there are, no doubt, which are in their essence too serious to admit of any lightness of treatment but I cannot recognise Geometry as one of them. Nevertheless it will, I trust, be found that I have permitted myself a glimpse of the comic side of things only at fitting seasons, when the tired reader might well crave a moments breathing-space, and not on any occasion where it could endanger the continuity of a line of argument. Pitying friends have warned me of the fate upon which I am rushing they have predicted that, in thus abandon ing the dignity of a scientific writer, 1 shall alienate the sympathies of all true scientific readers, who will regard the book as a m iejeu d esprit, and will not trouble them selves to look for any serious argument in it. But it must be borne in mind that, if there is a Scylla before me, there is also a Charybdis and that, in my fear of being read as a jest, I may incur the darker destiny of not being read at all. In furtherance of the great cause which I have at heart the vindication of Euclid s masterpiece I am content to run some risk thinking it far better that the purchaser of this little book should read it, though it be with a smile, than that, with the deepest conviction of its seriousness of purpose, he should leave it unopened on the shelf. To all the authors, who are here reviewed, I beg to tender my sincerest apologies, if I shall be found to have transgressed, in any instance, the limits of fair criticism. To Mr. Wilson especially such apology is due partly because I have criticised his book at great length and with no sparing hand partly because it may well be deemed an impertinence in one, whose line of study has been chiefly in the lower branches of Mathematics, to dare to pronounce any opinion at all on the work of a Senior Wrangler. Nor should I thus dare, if it entailed my following him np f yonder mountain height which Jie has scaled, but which I can only gaze at from a distance it is only when he ceases c to move so near the heavens and comes down into the lower regions of Elementary Geometry, which I have been teaching for nearly five and-twenty years, that I feel sufficiently familiar with the matter in hand to venture to speak...

-

Euclid And His Modern Rivals

Charles L. Dodgson

Paperback (Lindemann Press, Oct. 29, 2014)Many of the earliest books, particularly those dating back to the 1900s and before, are now extremely scarce and increasingly expensive. We are republishing these classic works in affordable, high quality, modern editions, using the original text and artwork.

-

Euclid and His Modern Rivals

Lewis Carroll

Paperback (TheClassics.us, Sept. 12, 2013)This historic book may have numerous typos and missing text. Purchasers can usually download a free scanned copy of the original book (without typos) from the publisher. Not indexed. Not illustrated. 1885 edition. Excerpt: ... Rivals: it is in quality, not in quantity, that they claim to supersede you. Your methods of proof, so they assert, are antiquated, and worthless as compared with the new lights. Eue. It is to that very point that I now propose to address myself: and, as we are to discuss this matter mainly with reference to the wants of beginners, we may as well limit our discussion to the subject-matter of Books I and II. Min. I am quite of that opinion. Euc. The first point to settle is whether, for purposes of teaching and examining, you desire to have one fixed logical sequence of Propositions, or would allow the use of conflicting sequences, so that one candidate in an examination might use X to prove J, and another use Y to prove X--or even that the same candidate might offer both proofs, thus 'arguing in a circle.' Min. A very eminent Modern Rival of yours, Mr. Wilson, seems to think that no such fixed sequence is really necessary. He says (in his Preface, p. 10) 'Geometry when treated as a science, treated inartificially, falls into a certain order from which there can be no very wide departure; and the manuals of Geometry will not differ from one another nearly so widely as the manuals of algebra or chemistry; yet it is not difficult to examine in algebra and chemistry.' Euc. Books may differ very 'widely' without differing in logical sequence--the only kind of difference which could bring two text-books into such hopeless collision that the one or the other would have to be abandoned. Let me give you a few instances of conflicting logical sequences in Geometry. Legendre proves my Prop. 5 by Prop. 8, 18 by 19, 19 by 20, 27 by 28, 29 by 32. Cuthbertson proves 37 by 41. Reynolds proves 5 by 20. When Mr. Wilson has produced similarly conflicting...

-

Euclid and His Modern Rivals - Primary Source Edition

Lewis Carroll

Paperback (Nabu Press, Feb. 24, 2014)This is a reproduction of a book published before 1923. This book may have occasional imperfections such as missing or blurred pages, poor pictures, errant marks, etc. that were either part of the original artifact, or were introduced by the scanning process. We believe this work is culturally important, and despite the imperfections, have elected to bring it back into print as part of our continuing commitment to the preservation of printed works worldwide. We appreciate your understanding of the imperfections in the preservation process, and hope you enjoy this valuable book.

-

Euclid and His Modern Rivals

Lewis Carroll

Paperback (Ulan Press, Aug. 31, 2012)This book was originally published prior to 1923, and represents a reproduction of an important historical work, maintaining the same format as the original work. While some publishers have opted to apply OCR (optical character recognition) technology to the process, we believe this leads to sub-optimal results (frequent typographical errors, strange characters and confusing formatting) and does not adequately preserve the historical character of the original artifact. We believe this work is culturally important in its original archival form. While we strive to adequately clean and digitally enhance the original work, there are occasionally instances where imperfections such as blurred or missing pages, poor pictures or errant marks may have been introduced due to either the quality of the original work or the scanning process itself. Despite these occasional imperfections, we have brought it back into print as part of our ongoing global book preservation commitment, providing customers with access to the best possible historical reprints. We appreciate your understanding of these occasional imperfections, and sincerely hope you enjoy seeing the book in a format as close as possible to that intended by the original publisher.