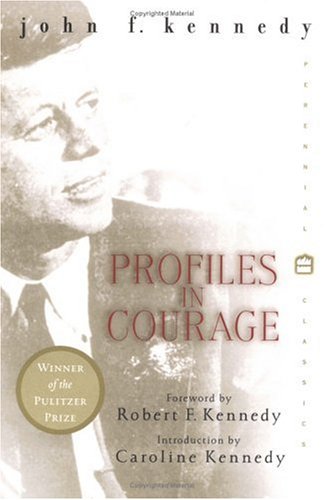

Profiles in Courage

John F. Kennedy

Hardcover

(HarperCollins, Oct. 1, 2006)

In 1954-1955, John F. Kennedy's active role as a Senator in the affairs of the nation was interrupted for the better part of a year by his convalescence from an operation to correct a disability incurred as skipper of a World War II torpedo boat. He used his "idle" hours to great advantage; he rediscovered, and did intensive research into, the courage and patriotism of a handful of Americans who at crucial moments in history had revealed a special sort of greatness: men who disregarded dreadful consequences to their public and private lives to do that one thing which seemed right in itself. These men ranged from the extraordinarily colorful to the near-drab; from the born aristocrats to the self-made. They were men of various political and regional allegiances—their one overriding loyalty was to the United States and to the right as God gave them to see it. There was John Quincy Adams, who lost his Senate seat and was repudiated in Boston for his support of his father's enemy Thomas Jefferson; Sam Houston, who performed political acts of courage as dramatic as his heroism on the field of battle; Thomas Hart Benton, whose proud and sarcastic tongue fought against the overwhelming odds that insured his political death; and Edmond Ross who "looked down into his open grave" as he saved President Johnson from an impeachment; and Norris of Nebraska; and Taft of Ohio; and Lamar of Mississippi (who did as much as any one man to heal the wounds of civil war). There was Daniel Webster, scourged for his devotion to Union by the most talented array of constituents ever to attack a Senator. For the most part Kennedy's patriots are United States Senators, but he also pays tribute to such men as Governor Altgeld of Illinois and Charles Evans Hughes of New York. And in the opening and closing chapters, which are as inspiring as they are revealing, Kennedy draws on his personal experience to tell something of the satisfactions and burdens of a Senator's job—of the pressures, both outward and inward—and of the standards by which a man of principle must work and live. John F. Kennedy has used wonderful skill in transforming the facts of history into dramatic personal stories. There are suspense, color and inspiration here, but first of all there is extraordinary understanding of that intangible thing called courage. Courage such as these men shared, Kennedy makes clear, is central to all morality—a man does what he must in spite of personal consequences—and these exciting stories suggest the thought that, without in the least disparaging the courage with which men die, we should not overlook the true greatness adorning those acts of courage with which men must live.